Edwin Corle (1906–1956) was a moderately successful American author of both fiction and nonfiction. He never wrote a best seller, none of his work entered the academic cannon, and today he is largely forgotten. He is also one of my favorite fiction writers.

Corle’s books, whether fiction or nonfiction, are set mainly in the desert regions of the American west, and this is why I first became aware of his work. I first encountered Corle’s writing when I was twelve years old, though I had probably seen his name previously in my collection of back issues of Desert Magazine. During a family vacation in Yosemite, I discovered a book titled Death Valley and the Creek Called Furnace (1962) which combined Corle’s prose with Ansel Adams’s photographs of the valley. Being a complete Death Valley fanatic, I had to have it. Corle’s contribution to the volume was actually a chapter excerpted from his Desert Country (1941). His accounts of people and events in the valley’s early history are highly colored and emphasize comedy rather than tragedy; strict historians could find many faults with his versions of events, but it was the sort of writing about the desert that appealed to my twelve-year-old sensibilities. This book is still in print, probably because of the Adams photographs, and can be ordered from Amazon. (I don’t care that much for Adams’s black and white photographs of Death Valley—he somehow manages to make the desert look cold.)

Some years later, in my late teens, my thoughts turned again to Corle; why, I no longer recall. Fortunately, I discovered that the public library in Whittier, California, where I grew up, had a complete or nearly complete collection of Corle’s novels, and I eventually read them all. Later, in the 1980’s, when I finally had a job that provided some disposable income, I collected, reread, and again enjoyed Corle’s seven novels and his collection of short stories, Mojave. I have reread most of them one or more times since.

The best known and most successful of Corle’s novels, and the only one that is still in print, in a 1971 edition, is Fig Tree John (Liveright, 1935), which is loosely based on the life of a well known and rather eccentric Indian who lived and grew figs at a spring by the western shore of the Salton Sea in Southern California in the early twentieth century. The real Fig Tree was a Desert Cahuilla named Juanito Razon, but Corle made his fictional Indian a renegade Apache with a violent past, a grudge against all whites, and a violent end. Many of those who remembered the historical Fig Tree were upset by Corle’s fictionalization. A comparison of fictional and historical characters can be found in Peter G. Beidler’s Fig Tree John: An Indian in Fact and Fiction (1977, University of Arizona Press).

My favorites among Corle’s novels are Burro Alley and Three Ways to Mecca. The two books are connected by a central character, John Lackland, a vagabond philosopher who struggles to understand the nature of time, space, and the ego. Lackland is, to a significant extent, the person I wanted to be in my late teens and early twenties. Burro Alley (Duell, Sloan & Pierce, 1938) is set in Santa Fe, my current home, in 1937. It describes a twelve-hour period, from 5PM to 5AM, in which characters from diverse backgrounds meet and interact in the blocks surrounding the Plaza. The cast includes Floriano, the town drunk; Amador Vigil, a gay male prostitute; Mrs. Tulsa, the alcoholic floozy wife of an oil-rich Oklahoma Indian; Max the Mauler, a prizefighter and killer on the lam; the aforementioned John Lackland, who is hitchhiking to the west coast to catch a freighter to India; and a bunch of New York “swells”—artists, collectors, musicians—staying at the upscale “La Paloma” hotel; in a addition to a host of other visitors and locals. The center of the action is Cielo Azul (Blue Heaven) a little cantina located on Burro Alley, a one-block street just west of the Plaza, where people allegedly tethered their burros in the nineteenth century. The burros are long gone, except for a statue at the corner of San Francisco street, and there are no dive bars. The area around Santa Fe’s plaza is the high rent district today, filled with museums, galleries, and restaurants. To find a dive like Cielo Azul, you’d have to head out to Airport Road.

Three Ways to Mecca (Duell, Sloan & Pierce, 1947) is both a prequel and a sequel to Burro Alley: a central section set in Paris in 1930 is bracketed by two outer sections set in Southern California in the 1946. In the Parisian section, Oliver Walling, an American college student and would-be writer, is befriended and mentored by an older American expat, John Lackland, already embarked on his studies of space and time. In the California sections, Walling, now a successful author (modeled, in some respects, on Corle himself), deals with the stresses of his professional and personal life by purchasing and wearing a dog suit. Also in the mix are crooked literary agents, a Czech film director, and a wealthy widow who is being courted by a Viennese psychiatrist and a Theosophist bishop, both of whom are eager get their hands on her money to further their own ambitions. Both the bishop and the psychiatrist claim that they can cure Walling’s problems and thus relieve him of his need to wear the dog suit, though Walling is happy in his suit and feels no need to be cured. Enter John Lackland, who sorts out matters in short order, both for the widow and for Walling, explaining his theory of the “three ways to Mecca,” meaning paths to personal fulfillment.

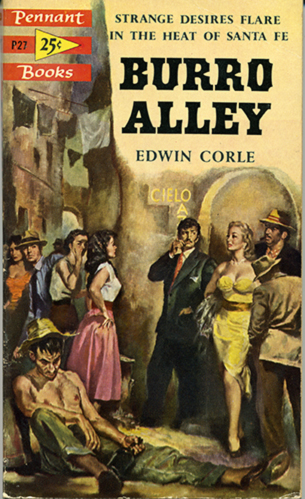

What brought Corle to mind this week is that I recently purchased a copy of the 1953 paperback edition of Burro Alley as a gift for a friend. As you can see from the lurid cover, the publisher of this cheap mass-market paperback has repackaged Corle’s novel as a piece of noir-ish pulp fiction. Anyone who bought the book based on its cover would have been deeply disappointed—there’s no explicit sex and only a little violence at the end.

Corle is not a great stylist—he tells his stories in a straightforward way in plain language. The author he most reminds me of, in terms of style, content, and attitude among his contemporaries, is Steinbeck. Occasionally, his prose may be a bit clunky. But he tells entertaining stories and populates them with interesting, often compelling, characters, and that, rather than linguistic virtuosity, is what I want from a novel. If your tastes are similar to mine, you should look him up. Most of his books are available on Amazon at reasonable prices, and you may find at least his more popular titles in your local library.

Other Books by Edwin Corle:

Fiction

- Mojave, a Book of Stories (Liveright, 1934)

- People on the Earth (Random House, 1937)

- Solitaire (E.P. Dutton, 1940)

- Coarse Gold (E.P. Dutton, 1942)

- In Winter Light (Duell, Sloan & Pierce, 1949)

- Billy the Kid (Duell, Sloan & Pearce, 1953)

Nonfiction

- Desert Country (Duell, Sloan, & Pierce, 1941)

- Listen, Bright Angel (Duell, Sloan & Pierce, 1946)

- John Studebaker, an American Dream (E.P. Dutton, 1948)

- The Royal Highway (El Camino Real) (Bobbs-Merrill, 1949)

- The Gila, River of the West(Rinehart & Company, 1951)

Thanks for the article. I, too, am a fan of Corle’s, and my introduction came in the 1960s with Desert Country. I lived in Santa Fe in the 60s and 70s, but wasn’t until a few years ago that I read Burro Alley, which is now one of my favorite novels. It would have made a fine noir-ish film. Corle was deeply interested in cosmology, and I read Desert Country at a time when I was also reading Sir James Jeans and Sir Arthur Eddington’s writing on space and time. Corle, I believe, references them in Desert Country.